vol.

012

MARCH

2016

vol.012 / Roundtable

Grasping the Unseen with Both Hands

Jun Aoki (architect) × Reijiro Tsumura (noh actor) × Haruka Kojin (contemporary artist)

Moving on to a place where you’ve eliminated the self

Aoki: Tsumura san’s comment just now about “eliminating the actor’s self by putting on a mask” made a big impression on me. When I’m designing something, I too try to take my ego out of the equation. I always try to be conscious of the extent to which I can depart from a point that’s not about me and how much I can erase me from the design. Well, it’s like lowering my guard and putting myself in the other person’s shoes. If I then feel as though their aesthetic sense has overpowered mine, there’s actually nothing more to think about. Of course, in architecture there are architectural styles, so you have to have a solid grasp on those, but that’s just technical stuff. I believe that it’s far more important to ensure that you transcend your self and put yourself in the other person’s place, because you’ll end up with something much better.

Tsumura: I understand really well how you feel. When I was young, my ego got in the way, because I’d think, “I want to play it this way.” But because I didn’t have enough technical ability, it wouldn’t go the way I wanted, so I often struggled. However, having reached this age, I’ve experienced almost all of the plays in the repertoire, so I’ve developed the technical ability, like a kind of pattern of movements, which means I know where I should stand in each case. Now, I can perform that pattern without conscious thought. I’m basically just a kind of vessel. But I actually get less tired now than I did when I was young.

Aoki: I wonder what it’s like inside your head when you’re performing that pattern of movements.

Tsumura: So do I (laughs). For example, as the shite (main character), I chant the vocal and dance, but of course I have to make sure that the rhythm fits with the hayashi (the musical accompaniment in a Noh performance). However, there are still times when I just can’t get it to fit right. When that happens, I inevitably get hung up on it. So when I was young — well, in my 50s, anyway (laughs) — I wanted to drag the hayashi-kata (instrumentalists) along with me, even though I was still immature. I don’t get that urge any more, though (laughs). Rather, I have a stronger sense that the program is a building that has been assigned to me, so I just have to function within those four walls.

Aoki: A building? (laughs) That’s interesting.

Tsumura: It’s not just in Noh; it’s the same when I’m performing with contemporary dancers, for example. We rehearse, but I don’t decide anything in detail in rehearsal. If I’ve got a sense of ego about it, thinking “I should perform it this way,” then it won’t come together. So we react against each other, based on the atmosphere in that place at that precise moment. It goes much better when I just go with it and let my body react freely and unreservedly to what my counterpart brings to their performance. And that’s why it looks to those around me as though I’ve meticulously planned the performance (laughs). That’s the absolute ideal.

Kojin: I haven’t reached quite the same state of mind as you two, but I guess I’ve felt for a long time that my works aren’t me. It’s the same with The day you will find the guy’s face in the sky. I just think of myself as the medium; the feelings that the work engenders are intrinsic to the individual viewer.

Tsumura: In art, there can be a sense of ownership over one’s own work, but you don’t have that.

Kojin: That’s right. For me, the most important thing is that art boils down to what feelings it triggers in each individual viewer.

Tsumura: Is that so? I too just think of myself as the medium that connects the work to the audience.

Kojin: So you feel that way as well? That’s why I always feel that I’m confronting contradictions. It’s like, “What do I have to explain about this work, even though it’s not me?” (laughs). I translate my ideas into reality as part of the group “Mé” and in the process of producing the work, I always feel really conflicted about how to share with the others my feelings and preferences that are hard to put into words, as well as when to let those things go.

Aoki: There’s a sense that a work doesn’t become something that I’ve made simply because I happen to have discovered it and experienced it for myself. Well, my field is architecture, so there’s time for trial and error between the discovery and completion, but with Tsumura san, for example, each performance is a one-off, so it’s really incredible.

Tsumura: There’s always the frustration that I can’t regard myself objectively. It’s probably to do with wearing a mask. You can’t see the angle of the mask for yourself. Even if you look in the mirror, you can’t see unless you raise your face slightly. So I have to get someone else to check which is the most appropriate posture. Even the angle of the basic postures differs from one mask to another, so I have to identify the standard ones by adjusting them each time and then make sure my body remembers them. But once it’s the actual performance, my feelings come into play and my postures gradually go to pieces. That’s why it’s so difficult.

Aoki: You’re achieving the pinnacle of perfection in Mai performance despite being unable to regard yourself objectively.

Joining the old to the new

Kojin: I hope that one day I’ll achieve the state of mind that you’ve both reached.

Tsumura: Things do start to become clearer when you do something for a long time. (laughs)

Kojin: Oh, I just remembered something from when I was creating the guy’s face. At dusk, crows suddenly start to fly around the sky in big flocks.

Aoki: When you say crows, you mean common or garden crows?

Kojin: Yes. The crows that you usually see living quite isolated lives, despised by humans. But when they flock together, you can see this incredible teamwork, and I found that really interesting. Because it occurred to me that you get moments just like that in the human world, too. Everyone lives separate lives, facing various struggles and difficulties. But I think that everyone’s experienced one of those moments when something makes you feel like you’re on the same wavelength as everyone else. Just like the crows, you forget that you’re an individual and you just come together with everyone else as part of a single life form. I want to create moments like that through art and it would be great if there were more and more opportunities for that.

Aoki: I think Tokyo has many faces and is quite varied, and that variety includes a diverse array of times and eras. I don’t want to be involved in scrap-and-build that makes every single building look like the next; my vision is for something more akin to grafting one tree onto another. The Hokke-do hall at Nara’s Todai-ji Temple is actually made up of two structures joined together: the shodo (image hall), a building with a hipped roof, which was built during the Nara period, and the raido (worship hall), a building with a hip-and-gable roof, which was renovated during the Kamakura period. They’ve been grafted together to create an exquisitely beautiful structure. That’s the sort of thing I mean, adding new things to old things but keeping their diversity. By cutting an old rootstock and grafting a new, young plant onto it, the original root rejuvenates and becomes more vigorous too; I think that if we could create more and more environments and cultures like that, we could really enrich communities.

Tsumura: You’re right, Aoki san, Tokyo certainly is home to a huge mix of things from different times and eras, and its people are diverse as well. I sometimes work in contemporary theater, dancing with contemporary dancers in their 20s and 30s, but we have a pretty equal relationship. At a time when the term “global society” is being bandied about so much, I think it’s important for everybody to be able to live their own lives as they wish, achieving freedom as they perceive it to be.

Kojin: Noh, architecture, art. These really are forms of culture that bring people together in a shared experience that transcends time, age, and race.

Tsumura: There’s a Noh play by Zeami called Takasago. It’s a very auspicious play, featuring the spirits of wedded pines — a pair of pine trees destined to remain together for eternity — that take human form as an elderly couple. It depicts the essential elements of human happiness. It’s a play that I think is really worth seeing in this day and age.

Aoki: Wonderful. Takasago is the perfect note on which to bring our roundtable to a close.

Tsumura: (laughs). Please do come and watch.

-

Jun Aoki

Born in 1956 in Kanagawa. Founded Jun Aoki & Associates in 1991. He works in a variety of areas, from private housing to public buildings and commercial facilities. His leading works include Mamihara Bridge, S, Fukushima Lagoon Museum, Louis Vuitton Omotesando, and Aomori Museum of Art. His latest book, Jun Aoki Complete Works 3 (INAX Publications) that archived his projects from 2005 to 2014, published in this February.

http://www.aokijun.com/en/news/ -

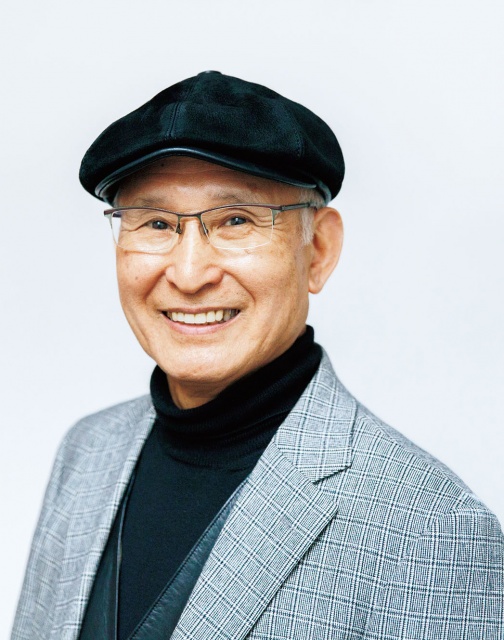

Reijiro Tsumura

Born in 1942 in Fukuoka. Began training under the Noh actor Kimiko Tsumura while still at university. Succeeded Kimiko Tsumura as head of Ryokusenkai in 1974. As well as performing classical and new Noh plays and working in collaboration with contemporary theater, he has been teaching, producing, and performing overseas in recent years as an Ambassador for Cultural Exchange under the auspices of the Agency for Cultural Affairs. His major publications include Noh ga wakaru 100 no kiiwaado [100 Key Words for Understanding Noh] (Shogakukan) and the photographic anthology Bugen [Bugen: Dancing Illusion of Noh] (Being Net Press).

http://www.ryokusenkai.net/profile.html -

Haruka Kojin

Born in 1983 in Hiroshima. In her installations, she intuitively finds otherworldly spaces in everyday scenery and recreates them as phenomena in art museum exhibition spaces and the like. She has presented her works both within Japan and overseas, including in the United States and Brazil. Since 2012, she has been a member of the contemporary art collective “Mé” with Kenji Minamigawa and Hirofumi Masui of the expressive activity team “wah document.” She is mainly involved in planning.

http://www.scaithebathhouse.com/en/artists/haruka_kojin/

Editing & Written by Nanae Mizushima

Photography: Sayuki Inoue

Special Thanks: sonorium, Tsuribori Musashinoen

Translation: Office Miyazaki, Inc.